Perhaps better known as "Tsingtao," thanks to the use of the old spelling that appears on millions of bottles of China's most famous beer, this city on the Yellow Sea is a fabulous destination for its clean ocean air, beaches, mountainous landscape and German colonial-era architecture, not to mention the aforementioned brew and the Shandong seafood dishes that go so well with it.

The city also has its inevitable fast-paced modern side, and since it was chosen to host the 2008 Olympics sailing events, it is enjoying an across-the-board upgrading of facilities in anticipation of waves of new visitors. Qingdao isn't new to the tourist game, however, as it's long been favored as a summer-time escape from Beijing's hot and dusty dog days.

Qingdao's deep water harbor and proximity to Korea and Japan have long made it a strategic port (hence the interest of the Germans), and immigrants and visitors have given the city an additional international twist: Why not try a little kimchi on your bratwurst instead of saurkraut? It all goes down well with a cool Tsingtao beer, brewed with spring water from the holy Taoist mountain Lao Shan, which makes for a beautiful day of hiking and taking the spectacular views.

History

Qingdao was little more than a fishing village in a scenic bay before the end of the 19th century. By 1891, the Manchu Qing Dynasty had decided to exploit the bay's strategic position and turn it into a naval base, but the tragic farce of the Boxer Rebellion unleashed a series of events that would deliver Qingdao to the Germans, eager for a stake in East Asia.

The Boxers consisted of Chinese who'd had enough of seeing their country pushed around by European colonial powers while the Qing leadership seemed to stand by helplessly. The Empress Dowager Cixi, who held power in Beijing while her young imperial ward stood in as figurehead, cynically attempted to redirect the Boxer's anger at the Qing toward foreigners.

It worked for a short while, and the Boxers attacked and killed a number of foreigners, as well as foreign-influenced Chinese (for example, Christian converts) before the vastly superior militaries of England, France, Germany and the United States came into play. After besieging the foreighn legation in Beijing in 1900, the Boxers were crushed by an international force and Cixi had to flee Beijing in disguise.

By that time, Qingdao had already fallen under German domination, thanks to Kaiser Wilhelm II's exploitation of the murder of two German missionaries in 1897. Germany easily forced the hapless Qing Dynasty to grant a 99-year lease to Qingdao, and they immediately moved in and started building (and brewing beer).

Germany had big plans in East Asia, but the onset of World War I sank those hopes. The ambitious Japanese took advantage of the outbreak of war in Europe to seize Qingdao in 1914, getting an assist from Great Britain, which was only too happy to damage the Kaiser in any way possible. After the war ended, China suffered yet another humiliation at the hands of the Great Powers of the time, as the Treaty of Versailles granted Japan continued rule of the former German colonial outpost.

This lead to another popular outcry from the Chinese, with the "May Fourth Movement" protests in Beijing stirring nationalist pride and anti-foreign feeling. Many see this period as setting the stage for the eventual triumph of the Chinese communists who, at that time, were beginning to organize. Qingdao did, return to China in 1922, only to be invaded by the Japanese in 1938 and held for the duration of the Sino-Japanese War.

The city has since weathered the turbulent times surrounding the establishment of the PRC and the Cultural Revolution and emerged as China's fourth largest port and the center of the Shandong Pinensula's booming economy while retaining the charm of a seaside resort with a unique architectural heritage. Spend a few days in Qingdao, and it's easy to see why it was chosen as one of China's Olympic cities.

Climate

Qingdao enjoys coastal weather—mild and moist—with summer months in the mid- to upper 20sº C (upper 70s to mid-80sº F). January is the coldest month with the temperature hovering around freezing. June and July are the rainy months and August brings warm water temperatures perfect for swimming at the beach. The transitional seasons of spring and fall are very pleasant.

Xi'an

Xi'an was once a major crossroads on the trading routes from eastern China to central Asia, and vied with Rome and later Constantinople for the title of greatest city in the world. Today Xi'an is one of China's major drawcards, largely because of the Army of Terracotta Warriors on the city's eastern outskirts.

Uncovered in 1974, over 10,000 figures have been sorted to date. Soldiers, archers (armed with real weapons) and chariots stand in battle formation in underground vaults looking as fierce and war-like as pottery can. Xi'an's other attractions include the old city walls, the Muslim quarter and the Banpo Neolithic Village - a tacky re-creation of the Stone Age. By train, Xi'an is a 16 hour journey from Beijing. If you've got a bit of cash to spare, you can get a flight.

Shanghai

Although the lights have been out for quite some time, Shanghai once beguiled foreigners with its seductive mix of tradition and sophistication. Now Shanghai is reawakening and dusting off its party shoes for another silken tango with the wider world.

In many ways, Shanghai is a Western invention. The Bund, its riverside area, and Frenchtown are the best places to see the remnants of its decadent colonial past. Move on to temples, gardens, bazaars and the striking architecture of the new Shanghai.

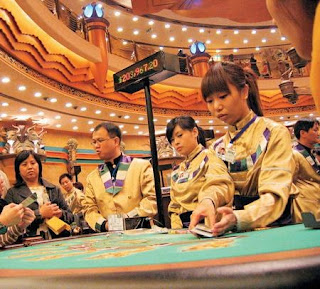

Macau The charm city of china

Macau may be firmly back in China's orbit, but the Portuguese patina on this Sino-Lusitanian Las Vegas makes it a most unusual Asian destination. It has always been overshadowed by its glitzy near-neighbour Hong Kong - which is precisely why it's so attractive.

Macau's dual cultural heritage is a boon for travellers, who can take their pick from traditional Chinese temples, a spectacular ruined cathedral, pastel villas, old forts and islands that once harboured pirates. A slew of musuems will tell you how it all came about.

Hong Kong has the big city specials like smog, odour, 14 million elbows and an insane love of clatter. But it's also efficient, hushed and peaceful: the transport network is excellent, the shopping centres are sublime, and the temples and quiet corners of parks are contemplative oases.

Hong Kong has enough towering urbanity, electric streetscapes, enigmatic temples, commercial fervour and cultural idiosyncrasies to utterly swamp the senses of a visitor, and enough spontaneous, unexpected possibilities to make a complete mockery of any attempt at a strictly organised itinerary.

Beijing

If your visions of Beijing are centred around pods of Maoist revolutionaries in buttoned-down tunics performing t'ai chi in the Square, put them to rest: this city has embarked on a new-millennium roller-coaster and it's taking the rest of China with it.

The spinsterish Beijing of old is having a facelift and the cityscape is changing daily. Within the city, however, you'll still find some of China's most stunning sights: the Forbidden City, the Summer Palace, Temple of Heaven Park, the Lama Temple and the Great Wall, to name just a few.

Emperor Qin Shihuang's Mausoleum and the Terra-cotta Warriors and Horses Museum

发帖者 China Tourism 标签: Emperor, Horses Museum, Mausoleum, Qin Shihuang, Terra-cotta WarriorsEmperor Qin Shihuang's Mausoleum and the Terra-cotta Warriors and Horses Museum

Emperor Qin Shihuang (259-210B.C.) had Ying as his surname and Zheng as his given name. He name to the throne of the Qin at age 13, and took the helm of the state at age of 22. By 221 B.C., he had annexed the six rival principalities of Qi, Chu, Yan, Han, Zhao and Wei, and established the first feudal empire in China's history.

In the year 221 B.C., when he unified the whole country, Ying Zheng styled himself emperor. He named himself Shihuang Di, the first emperor in the hope that his later generations be the second, the third even the one hundredth and thousandth emperors in proper order to carry on the hereditary system. Since then, the supreme feudal rulers of China's dynasties had continued to call themselves Huang Di, the emperor.

After he had annexed the other six states, Emperor Qin Shihuang abolished the enfeoffment system and adopted the prefecture and county system. He standardized legal codes, written language, track, currencies, weights and measures. To protect against harassment by the Hun aristocrats. Emperor Qin Shihuang ordered the Great Wall be built. All these measures played an active role in eliminating the cause of the state of separation and division and strengthening the unification of the whole country as well as promotion the development of economy and culture. They had a great and deep influence upon China's 2,000 year old feudal society.

Emperor Qin Shihuang ordered the books of various schools burned except those of the Qin dynasty's history and culture, divination and medicines in an attempt to push his feudal autocracy in the ideological field. As a result, China's ancient classics had been devastated and destroy. Moreover, he once ordered 460 scholars be buried alive. Those events were later called in history “the burning of books and the burying of Confucian scholars.”

Emperor Qin Shihuang, for his own pleasure, conscribed several hundred thousand convicts and went in for large-scale construction and had over seven hundred palaces built in the Guanzhong Plain. These palaces stretched several hundred li and he sought pleasure from one palace to the other. Often nobody knew where he ranging treasures inside the tomb, were enclosed alive.

Emperor Qin Shihuang's Mausoleum has not yet been excavated. What looks like inside could only be known when it is opened. However, the three pits of the terra-cotta warrior excavated outside the east gate of the outer enclosure of the necropolis can make one imagine how magnificent and luxurious the structure of Emperor Qin Shihuang's Mausoleum was.

No.1 Pit was stumbled upon in March 1974 when villagers of Xiyang Village of Yanzhai township, Lintong County, sank a well 1.5km east of the mausoleum. In 1976, No.2 and 3 Pits were found 20m north of No.1 Pit respectively after the drilling survey. The terra-cotta warriors and horses are arrayed according to the Qin dynasty battle formation, symbolizing the troops keeping vigil beside the mausoleum. This discovery aroused much interest both at home and abroad. In 1975, a museum, housing the site of No.1 and covering an area of 16,300 square meters was built with the permission of the State Council. The museum was formally opened to public on Oct.1, the National Day, 1979.

No.1 Pit is 230 meters long from east to west, 62m wide from north to south and 5m deep, covering a total area of 14,260 square meters. It is an earth-and-wood structure in the shape of a tunnel. There are five sloping entrances on the eastern and western sides of the pit respectively. The pit is divided into eleven corridors by ten earthen partition walls, and the floors are paved with bricks. Thick rafters were placed onto the walls (but now one can only see their remains), which were covered with mats and then fine soil and earth. The battle formation of the Qin dynasty, facing east. In the east end are arrayed three lines of terra-cotta warriors, 70 pieces in each, totaling 210 pieces. They are supposed to be the van of the formation. Immediately behind them are 38 columns of infantrymen alternating with war chariots in the corridors, each being 180m long. They are probably the main body of the formation. There is one line of warriors in the left, right and west ends respectively, facing outwards. They are probably the flanks and the rear. There are altogether 27 trial trench, it is assumed that more than 6,000 clay warriors and horses could be unearthed from No.1 Pit.

No.2 Pit sis about half the size of No.1 Pit, covering about 6,000 square meters Trail diggings show this is a composite formation of infantry, cavalry and chariot soldiers, from which roughly over 1,000 clay warriors, and 500 chariots and saddled horses could be unearthed. The 2,000-year-old wooden chariots are already rotten. But their shafts, cross yokes, and wheels, etc. left clear impressions on the earth bed. The copper parts of the chariots still remain. Each chariot is pulled by four horses which are one and half meters high and two metres long. According to textual research, these clay horses were sculptures after the breed in the area of Hexi Corridor. The horses for the cavalrymen were already saddled, but with no stirrups.

No.3 Pit covers an area of 520m2 with only four horses, one chariot and 68 warriors, supposed to be the command post of the battle formation. Now, No.2 and 3 Pits have been refilled, but visitors can see some clay figures and weapons displayed in the exhibition halls in the museum that had been unearthed from these two pits. The floors of both No.1 and 2 Pits were covered with a layer of silt of 15 to 20cm thick. In these pits, one can see traces of burnt beams everywhere, some relics which were mostly broken. Analysis shows that the pits were burned down by Xiang Yu, leader of a peasant army. All of the clay warriors in the three pits held real weapons in their hands and face east, showing Emperor Qin Shihuang's strong determination of wiping out the six states and unifying the whole country.

The height of the terra-cotta warriors varies from 1.78m, the shortest, to 1.97m, the tallest. They look healthy and strong and have different facial expressions. Probably they were sculpted by craftsmen according to real soldiers of the Qin dynasty. They organically combined the skills of round engraving, bas-relief and linear engraving, and utilized the six traditional folk crafts of sculpturing, such as hand-moulding, sticking, cutting, painting and so on. The clay models were then put in kilns, baked and colour-painted. As the terra-cotta figures have been burnt and have gone through the natural process of decay, we can't see their original gorgeous colours. However, most of the terra-cotta figures bear the trace of the original colours, and few of them are still as bright as new. They are found to be painted by mineral dyestuffs of vermilion, bright red, pink dark green, powder green, purple, blue, orange, black and white colours.

Thousands of real weapons were unearthed from these terra-cotta army pits, including broad knives, swords, spears, dagger-axes, halberds, bows, crossbows and arrowheads. These weapons were exquisitely made. Some of themes are still very sharp; analyses show that they are made of alloys of copper and tin, containing more than ten kinds of other metals. Since their surfaces were treated with chromium, they are as bright as new, though buried underground for more than 2,000 years. This indicates that Qin dynasty's metallurgical technology and weapon-manufacturing technique already reached quite a high level.

In December 1980, two teams of large painted bronze chariots and horses were unearthed 20 metres west of the mound of Emperor Qin Shihuang's Mausoleum. These single shaft four-horse chariots each comprises 3,462 spare parts, and has a body with two compartments, one behind the other, and an elliptical umbrella like canopy. The four horses harnessed to the chariot are 65-67 centimeters tall. The restored bronze chariots and horses are exact imitations of true chariot, horse and driver in half life-size.

The chariots and horses are decorated with coloured drawings against white background. They have been fitted with more than 1,500 pieces of gold and silvers and decorations, looking luxurious, splendid and graceful. Probably they were meant for the use of Emperor Qin Shihuang's soul to go on inspection. The bronze chariots and horses were made by lost wax casting, which shows a high level of technology. For instance, the tortoise-shell-like canopy is about 4mm thick, and the window is only 1mm thick on which are many small holes for ventilation. According to a preliminary study, the technology of manufacturing the bronze chariots and horses has involved casting, welding, reveting, inlaying embedding and chiseling. The excavation of the bronze chariots and horses provides extremely valuable material and data for the textual research of the metallurgical technique, the mechanism of the chariot and technological modeling of the Qin dynasty.

No.2 bronze chariot and horses now on display were found broken into 1,555 pieces when excavated. After two-and-half years' careful and painstaking restoration by archaeologists and various specialists, they were formally exhibited in the museum on October 1, 1983. No.1 bronze chariot hand horses are on display from 1988.